Telling the truth about 'sustainable commerce'

it's already there, we can embrace it right now - individually and collectively

Hey there 👋 it’s kev this time. We are Objet. We explore the intersection of consumerism, myth, satisfaction, desire, taste, joy, meaning and pride. Not specifically in that order. To brag at your next dinner, Objet is the french word for 'object' and should be pronounced 'OB-JEH'.

There is no such thing as sustainable commerce. We can't buy our way out of the climate crisis. We can't buy our way to happiness neither. Now, there are ways to feel better, more satisfied, more at peace: just buy dramatically less.

It's not easy. It does feel that everything truly worth experiencing in life are challenging anyway. As

wrote in Why An Easier Life Is Not Necessarily Happier: “if we aim indiscriminately at the frictionless life—then we simultaneously rob ourselves of the real satisfactions and pleasures that enhance and enrich our lives”.So, to everyone working, writing, preaching on sustainability and commerce, please, focus on telling the truth - even though it's hurting, it is pretty intuitive - we all have to buy dramatically less. Period.

I've been helping people buy things for more than a decade now. I even started an 'ethical fashion' ecommerce website back in 2011. Not only did we curate brands that were doing the minimum amount of harm, we also dedicated 10% of every sale to a micro-entrepreneur - via the french equivalent of Kiva back then, named Babyloan. We pushed that dynamic even further: customers themselves were able to choose which entrepreneur to finance while in the checkout process. We were feeling proud. Our tagline was: 'buy happy, help makers'.

My go-to destination these days, if I want to buy a new piece of clothing, is Centre Commercial. They have a few stores in Paris. It's been created by the founders of Veja - which you can think of the Patagonia of sneakers. And exactly like Patagonia: while they'd celebrate us buying a pair of their own sneakers instead of a Nike one [insert here pretty much any big corporate brand], they also stay intellectually honest. I've never heard them telling something along the lines of 'buy our sneakers to save the planet'. Why? Because “everything we make takes something from the planet we can’t give back” [let that sink in]; so we don't 'save' anything when we buy.

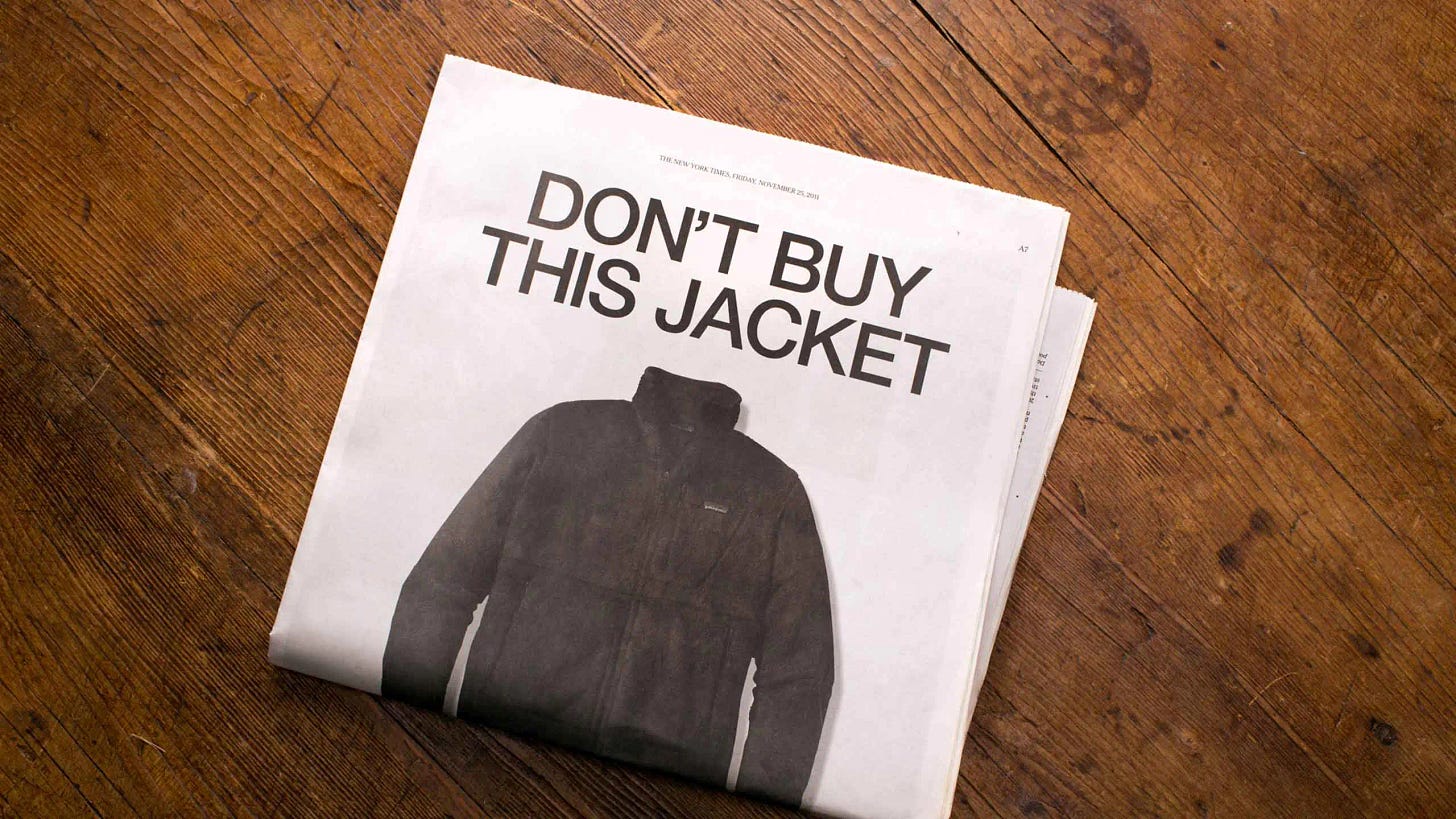

This campaign 👆 was designed to tackle the issue of consumerism head on. And there is absolutely no better way to say it than this:

to lighten our environmental footprint, everyone needs to consume less. Businesses need to make fewer things but of higher quality. Customers need to think twice before they buy.

So while I totally agree with

when he picks up 'sustainability' as one of the Seismic Waves of Gen Z Behavior I can't disagree enough on his 'sustainable commerce' example.Before diving in: Rex is an amazing writer. I haven't had the chance to meet him yet but we did exchange a few emails in the past. And obviously, I look forward to meeting him one day. His newsletter

- about how people and technology intersect - is frankly one of the few I enjoy reading the most. Most importantly, I always learn when reading him so I highly recommend it.Let me explain how I disagree with his 'sustainable commerce' example.

It starts strong: “It turns out that retail is very, very bad for the environment. Retailers are responsible for about 25% of global carbon emissions.” Then it goes on pointing out the absurdity of this industry: “in 2017, a Swedish power plant abandoned coal as a source of fuel, instead choosing to burn mountains of discarded clothing from H&M 🤦♂️”

At that point I was telling myself 'yep this is going to the right direction'. One last metric worth mentioning: “and consumers want change: according to McKinsey/Nielsen, 78% of people want to shop sustainably” And then he mentioned some 'solutions'. Right there I started to worry [yep I'm used to this narrative]. “On the shopping experience side, startups […] are embedding sustainability into checkout.”

I wondered 'oh, do they intercept the checkout to remind us the above metrics and encourage us to breathe, pause and think twice before completing that purchase?' hmm 🤔 of course not.

Consumers can donate 1% of their cart to an important cause […] and the brand will foot the bill. Brands are willing to do this because average order values go up 15%, conversion improves 11%, and cart abandonment rates drop 17%. Building sustainability into the retail experience is becoming tablestakes.

WTF! If 'average order values' goes up and 'conversion improves' it literally means: people are buying more; which causes more damage to the environment. The only way we could assure this behavior is good would be if we could prove that these additional purchases replaced some other ones that would have been made in worst places. But even in this scenario, while it'd be better than usual, sure, it's also worst than a straight 'no buy'. And nowhere do I see that hierarchy of impact clearly stated.

Let's emphasize that: if we were being honest in terms of sustainability, we should always first shout out the truth; at every occasion: we have to consume less. 'Fewer things of higher quality'. Very straight forward.

And yes, VCs [venture capitalists] are 100% capable of saying this out loud. At least if and when they want to be serious about sustainability. Want some proof? Well, I strongly recommend this whole discussion between Eric Newcomer and Albert Wenger.

To set up the ton,

wrote:Wenger has a strong point of view about where we’re headed: he argues that we’ve moved from the Industrial Age to the Knowledge Age and that we need to dramatically rethink society in light of that change.

More specifically towards our present topic, you can listen from 54min12sec onwards: “There are some things we have to stop doing […] like the random overconsumption of some stuff needs to stop for a while […] like people having 70 pairs of shoes”. Boom 💥

It is time to treat consumerism for what it is exactly: an addiction. No one described this better than Om in the Consumerism Curse:

Among the hardest things I have done in my life is to quit smoking. It has been over a decade since I last touched a cigarette, but I live with the effects of a 25-year habit, dealing with illnesses and issues that lead directly back to damage done by smoking. […] But there is one demon I have not been able to conquer, an addiction that is worse than nicotine: consumerism. For the past four years, every year, I make an effort to get rid of things and buy less. It is not easy to do — the machines of desire work constantly and are powerful. I looked at my own spending trends, and I am at about 25 percent of where I was four years ago. I have bought much fewer things and gotten rid of an average 10 things a month. And yet, it is not enough.

This graph definitely tells something interesting, or funny [sarcasm here], or plain dramatic about us:

Where do 'these powerful machines of desire' come from exactly? Well, it might have started just a century ago, in America in the 1920s, with Sigmund Freud’s nephew: Edward Bernays. Mathilde wrote about the intersection of psychoanalysis and consumerism, the invention of PR [Public Relations], and when Edward himself “envisioned consumerism as a tool to control masses. Consumerism would be the illusion of power, given to the masses. While an “enlighten despot” should rule.”.

Where does all this leave us? I think the message is crystal clear - on an individual level: we should think more and buy dramatically less.

On a business one, well, make fewer things of higher quality might be a good start. Om relates a quote from Becky Okell, one of Paynter co-founder - a brand I'm personally in love with; their Six Mile Tee might simply be the best t-shirt I ever owned: “We’re ultimately trying to make people re-think the way they buy clothes, whether it’s from us or anyone else. If we have 900 customers per year, but we inspire many more to re-think the way they buy clothing, then that’s a good job well done.”

What Jon - Deru's co-founder - says in just a few words at the very end of his interview with Early Majority resonated: “Building something that’s not just about consuming whilst still running a commercial business is the big conundrum at the moment.”

I started to reflect more and more on this quote: why is that? Is it because our most common definition of success revolves around scale? When did massive sales & mainstream become so mandatory? and why?

'Fewer things of higher quality' might become the mantra of tomorrow's commerce. And guess what: this is the most sustainable approach everyone can take. The alternative Buy low, sell low is getting uglier: “a similar, slow-burn reckoning is poised to occur in the e-commerce world. The buy low, sell low model that made Amazon, Walmart, Target, and major US retailers rich—and engendered a micro-economy of dropshippers—won’t be tenable for much longer. Temu, AliExpress, and its ilk can sell even lower.”

A few weeks ago “was the 10th anniversary of the Rana Plaza factory collapse. The building in Dhaka, Bangladesh was a sweat shop for garment workers, and when it collapsed more that 1100 people died and 2500 more were injured. It was a flashpoint for the industry, as garments with western labels were pulled out of the rubble: H&M, Mango, Primark, Matalan. The brands claimed they knew nothing of the conditions of the garment workers”. I agree with

in The New Vanguard of Quality:there is a growing community of people who care, who want to engage fully with a subject, who prefer slow to fast, who go deep and meaningful and long form and do not want to swipe, scroll, binge and release.

I do notice more and more people who care. I wonder what role exactly culture might play here. Longevity may seem like a more important definition of success in Japan for instance. Why so many of the world’s oldest companies are in Japan? It’s fascinating how often Japan comes in any discussion about caring for things, soul, meaning, crafting. I remember a Gestalten book I loved a few years ago in Berlin The Monocle Guide to Good Business and Japan really has its fair share of stories inside.

Sari asked “Good things don’t scale” in the latest

issue. Look how Japan resurfaces here with :Japan is full of these experiences, where art, curiosity, and craftsmanship yield tiny scattered wonders like “owl cafes,” micro arcades, plastic food shops, cotton candy shops, and the list goes one. I found myself wondering, why aren’t there 1000x more of these experiences in all societies? Why must the purpose of business be to scale, grow bigger, become franchises, squeeze in more seats, and compromise quality for automation and reach?

Sari highlighted this sentence many many years ago:

You walk down your high street. What do you prefer to see there? The economist will say: Walmart, Best Buy, the Gap. Scale economies — cheaper prices — better for “consumers”! But the human being will say: an independent cafe, a good bookshop, a boutique clothing store. Why? Because they offer many things that mega scale organizations don’t.

I was happy - and didn’t expect - to hear someone like

pointing out the challenge ahead for brands like The Hundreds: “a large motivation was to essentially go against what fashion has been doing in terms of contributing to waste in the world from a sustainable perspective”. It’s coming from 2h27min30sec onwards in his discussion with Tim Ferriss. The whole discussion is worth it. Sure, it’s coming from someone who’s always been immersed in the skateboarding scene, streetwear, punk & hiphop.The key lies in the level of intentionality we put in our decisions. Why are we doing what we're doing? Do I decide to go on auto-pilot and let the external 'machines of desire' dictate what should I value, desire and buy? or do I intentionally choose to decide by myself? to dare to pause for a little while and ask myself 'why' a few times?

Alec Leach used to be the fashion editor of the streetwear publication Highsnobiety. He wrote a book I can't recommend enough: 'The world is on fire but we're still buying shoes'. Mathilde highlighted his conclusions:

By taking ownership over our shopping habits, we can say no to this culture of non-stop newness, the relentless cycle of trends that keeps us buying way more than we really need, the war on our self-esteem that makes us feel like we’re never enough - and all the environmental destruction that comes with it.

[…]

Slowly but surely assembling a collection of things that we truly love. Hunting down that perfect piece, cherishing it for years to come, embracing the flaws it picks up along the way. It’s a win-win situation. Better for the planet, but better for us too.

“A central question we should all be asking both individually and collectively is”: How much is enough?

Regarding clothing, it looks like just a handful of new items a year. Lauren relates something I heard so many times: "I bought 82 new pieces of clothing, shoes and accessories in a single year – and still managed to feel badly dressed. (When you buy 82 things in a single year, you don’t spend much time thinking about what you’re acquiring.)”

Breaking free from rampant consumerism is demanding. Wanting better things is a muscle we need to train. In a short video,

explains Why we want the wrong things:Thin desires are ephemeral and easily influenced by external factors, while thick desires are rooted in our core beliefs and values. In order to take control of our desires and avoid being pushed and pulled in directions that aren’t true to ourselves, we must identify the difference between the two.

At the end of the day, this is exactly what Objet is all about: how to go from thin to thick desires.

Paul Graham describes perfectly in his Stuff essay the imbalance of power at play here:

The really painful thing to recall is not just that I accumulated all this useless stuff, but that I often spent money I desperately needed on stuff that I didn't. Why would I do that? Because the people whose job is to sell you stuff are really, really good at it. The average 25 year old is no match for companies that have spent years figuring out how to get you to spend money on stuff. They make the experience of buying stuff so pleasant that "shopping" becomes a leisure activity.

So we're building a tool that acts as a counter-power; that’s empowering. Objet lets us experience the true joy of ownership. From a consumption perspective, we might all learn the virtue of enoughness.

To embark on a journey towards a better relationship with objects:

… share Objet journal with a soulmate 👯

… subscribe to Objet journal to receive new posts 🛹

Thanks to Mathilde Baillet, Maxime Cattet, Om Malik, and Clayton Chambers for reading drafts of this.

Peace ✌️

I have been consuming less clothing for awhile, but it seems fabric quality is is getting worse and worse even if I don't pay under $20 for a garment. I have something for 2 years and the fabric is so thin I can see through it. I'd love to spend more for better fabric quality - but how do I even find that? Not in any of the stores I've been to in person. It's all very frustrating. I don't want to buy trash.

very interesting and very well documented. I wonder as well if things that are sold through ecommerce could not be just natively less about materials / goods and more about a certain kind of services / intelligence / digital layers around them. It won't solve 100% of the fact that when we shop = we transform input into output therefore 'consume' the planet to some extent but might be worth exploring in terms of business model. It's also a full reconsideration of business models from logistical standpoint, as well as the notion of profits. A lot of questions on which I'm not expert but definitely worth exploring as a citizen. Merci !